|

| MHE / MO / HME Standards Of Care Guide Authored by Harish Hosalkar, MD., MBMS,FCPS,DNB Pediatric Orthopedic Surgeon, Clinical Instructor, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA John Dormans, MD. The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, PA Click Here To View The Standards Of Care Clinical Informational Video Follow Up Companion To This Guide Diagnostic Tools Important features of orthopedic exam: |

It is important to follow each step of the exam during every office assessment of MHE (check the link for

Hereditary Multiple Exostoses: A Current Understanding of Clinical and Genetic Advances)

Hereditary Multiple Exostoses: A Current Understanding of Clinical and Genetic Advances)

Frequency of Follow-up

Note: Your child’s orthopaedist may recommend follow-up at different intervals, sometimes

every 3 months, sometimes a year or more, and can explain why that time frame is indicated.

Characterization of Lesions:

| Children should be followed up at 6-9 month intervals and sooner if there are any red flags | |

| in terms of sudden increase in size of the bump, pain, tingling, numbness, weakness, visible and progressive limp, limb deformities and length discrepancies | ||

| It is important to keep a regular follow-up of all cases even after skeletal maturity. Most | |

| patients have increased awareness of all the red flags to be watched for by this time and hence can keep a personal lookout for the same. A thorough exam can be performed by the clinician (including measurements) during the office visit. Radiographs should be repeated only when the bumps are symptomatic or growing. |

Note: Your child’s orthopaedist may recommend follow-up at different intervals, sometimes

every 3 months, sometimes a year or more, and can explain why that time frame is indicated.

Characterization of Lesions:

- Location: Whether the tumor is located in the limb bones, chest wall or ribs, skull, or any

other sites in the body.

| Pain: Is the lesion associated with pain? If yes: Please view the chronic pain section |

- Intensity: Can be assessed and documented in a lot of ways.

| On a pain scale of 1 to 10. | |

| Pain Tracker, all of which can be used as a tool to discuss pain with a child during | |

| an examination. |

- Quality:

| Do you experience pain on and off (intermittently) throughout the day, or all the | |

| time (constantly)? | ||

| Does the pain occur at specific times, or with specific activities (ex. Upon waking in | |

| the morning, when walking, etc.) | ||

| Is pain interfering with your general activities? | |

| Do you need to use special accommodations at work or school? | |

| Is pain affecting your mood? | |

| Do you take medications for pain, or use other treatments (i.e. heat, ice, rest). If | |

| so, are these treatments effective? | ||

| Tumor pain is often unrelenting, progressive, and often present during the night. | |

| Is there any shooting pain? (Suggestive of nerve compression) |

- Radiation: Pain radiating to upper or lower extremities or complaints of numbness,

tingling or weakness suggest neurologic compression and requires appropriate workup.

Onset:

How was the tumor noticed?

Was there any history of trauma?

When did the pain actually start?

Duration:

What has been the duration of this new lesion?

How long have the other lesions been around?

Progress: Whether the exostosis has remained the same, grown larger, or gotten smaller?

Associated symptomatology:

Gait and posture disturbances (especially during follow-up of skull or spinal lesions and in cases of limb-length discrepancies and deformities).

Any specific history of back pain. If yes, its complete characterization.

Change in bladder or bowel habits (for evidence of spinal lesions causing cord compression)

Gynecologic function alterations in girls with pelvic lesions.

Scoliosis may be associated with spinal lesions and may need to be monitored.

Night pain if present is a worrisome symptom and needs complete evaluation. Night pain is different than chronic pain in that the pain is not constant and

characteristically wakes the patient from sound sleep. Chronic pain on the other hand

is persistent and would interfere with the sleep pattern by making the patient

restless. Chronic night pain is especially common in MHE cases where the location of

the bump may cause pressure on the exostoses when lying down. Soft beds, air

cushions, lateral positioning and frequent turning may prove to be helpful in these

cases.

Neurologic symptoms may be associated spinal or skull lesions. More commonly, local compression of peripheral nerves due to expanding lesions is encountered in

arms and legs. In addition, several cases of Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy (RSD)

following MHE surgeries to knees and wrists have been noted. Many patients also

experience other nerve-related symptoms following surgery, including long-lasting

pain and sensitivity around surgical sites long after incisions have healed.

Bursa formation and resulting bursitis may occur as a result of the exostoses and should be recorded. A bursa is a fibrous sac lined with synovial membrane and filled

with synovial fluid and is found. The function of a bursa is to decrease friction

between two surfaces that move in different directions. Therefore, you tend to find

bursae at points where muscles, ligaments, and tendons glide over bones. These

bursae can be either anatomical (present normally) or may be developmental (when

the situation demands). The bursae can be thought of as a zip lock bag with a small

amount of oil and no air inside. In the normal state, this would provide a slippery

surface that would have almost no friction. A problem arises when a bursa becomes

inflamed. It loses its gliding capabilities, and becomes more and more irritated when

it is moved. Bursitis can either result from a repetitive movement or due to

prolonged or excessive pressure.

Diagnostic work-up

Physical examination.

A thorough physical examination of the patient is extremely important in the assessment of MHE

patients.

Radiographs

High quality plain radiographs (X-rays) (anteroposterior and lateral views) should be ordered in

cases presenting with exostoses. Standing postero-anterior and lateral views of the entire spine

on a three-foot cassette should be ordered when spinal lesions are suspected. Special views like

tangential views of the scapula may need to be ordered in some cases. Plain films help to localize

the lesion and give a fairly good idea about its size and dimensions in 2 planes. Also scanograms

help to assess the extent of limb-length discrepancy and its localization. Oblique views of the

spine and special skull views may be ordered in suspected cases.

Advanced Imaging

Radionucleide bone scan (bone scan) is sensitive to pathologies causing increased bone

activities within the skeleton. In combination with SPECT (single photon emission computed

tomography), it gives excellent localization of the area of increased uptake. This is extremely

useful in MHE to locate multiple lesions, especially those that are situated in deeper areas not

amenable to clinical palpation. Further imaging if required, can then be focused. Thallium and

PET (positron emission Tomography) scans are also modalities that can help define the

tumor metastasis especially in those rare cases of malignant degeneration.

Computed Tomography (CAT / CT scan)

CT scans are useful in visualizing the bony architecture particularly as an adjunct to plain

radiographs or bone scans. Thin slice CT cuts may be necessary in small lesions. Two and three-

dimensional reconstructions are possible and add to the information. Rarely the CT may be

combined with the myelogram to effectively delineate the size of the lesion especially for

intraspinal lesions.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

This is an excellent modality for defining the spinal cord, nerve roots, soft tissue structures and

cartilage. Cortical bone is not seen as well as compared with CT. Cartilage caps of the

exostoses and their compression effects on soft-tissues, nerves and adjacent vessels can be

very well delineated. It is a study of choice in suspected cases of malignant transformation. MRI

studies must be reserved for those cases in which clinical signs and symptoms deem them

appropriate. Clinicians must make a point to communicate clinical information and suspected

differential diagnosis to the radiologists.

Other Diagnostic Tools

Ultrasound

May be necessary to diagnose compression of arteries. The principle for ultrasound, or

ultrasonography, is the same as for underwater sonar or echo sounding. An apparatus sends an

ultrasonic wave through the body at a speed of about 1,500 meters per second. At the interface

between two types of tissue, the wave will be refracted or ‘broken up’, and part of the wave will

be reflected back and detected by the apparatus. The rest of the ultrasonic wave continues

deeper into the body, and is reflected as an echo from the surface of tissues lying further inside

the body. How much is reflected depends on the densities of the respective tissues, and thus

the speed of the sound wave as it passes through them. The time taken for the reflected wave

to return indicates how deep the tissue lies within the body. In this way, one obtains a picture of

the relative locations of the tissues in the body, in the same way that one may visualize the

contours of a school of fish with sonar. An ultrasound can help ascertain the status of the blood

flow through the arteries as well and is therefore important for assessment of suspected

compression.

EMG (Electromyography, myogram)

May be necessary in cases of suspected nerve damage

What is EMG

Electromyography (EMG) is a test that measures muscle response to nervous stimulation

(electrical activity within muscle fibers).

How the test is performed

A needle electrode is inserted through the skin into the muscle. The electrical activity detected

by this electrode is displayed on a monitor (and may be heard audibly through a speaker).

Several electrodes may need to be placed at various locations to obtain an accurate study. After

placement of the electrode(s), you may be asked to contract the muscle (for example, by

bending your arm). The presence, size, and shape of the wave form (the action potential)

produced on the monitor provide information about the ability of the muscle to respond when

the nerves are stimulated.

Each muscle fiber that contracts will produce an action potential, and the size of the muscle fiber

affects the rate (frequency) and size (amplitude) of the action potentials. A nerve conduction

velocity test is often done at the same time as an EMG.

Why the test is performed

EMG is most often used when people have symptoms of weakness and examination shows

impaired muscle strength. It can help to differentiate primary muscle conditions from caused

by neurologic disorders. EMG can be used to differentiate between true weakness and reduced

use due to pain or lack of motivation.

Histology

Clinical examination and Imaging findings can help establishing the diagnosis in most cases.

Biopsy should be performed when a malignant change is suspected.

Laboratory evaluation / Genetic Testing (Please also read the MHE Research

Foundations genetics section of the website.)

Test methods:

Sequence analysis of the EXT1 and EXT2 genes are offered as separate tests. Using genomic

DNA obtained from buccal (cheek) swabs or blood (5cc in EDTA), testing of EXT1 proceeds by bi-

directional sequence analysis of all 11 coding exons. The EXT2 gene consists of 15 exons, and

all coding exons (2-15) are sequenced in the analysis.

Test sensitivity:

In patients with MHE, mutations are found in approximately 80% of individuals. Of those in

whom mutations are identified, 70% of the mutations are found in the EXT1 gene and the

remaining 30% in the EXT2 gene. Thus, the method used to screen the EXT1 is expected to

identify approximately 60% of mutations in MHE. In individuals who are found to be negative on

analysis of the EXT1 gene, screening of the EXT2 gene will identify the molecular basis of the

disease in a further 25% of affected individuals. To date, there are no known distinguishing

features within the clinical diagnosis of MHE known to predict which gene is more likely to have a

mutation. Multiple exostoses can be associated with contiguous deletion syndromes, which are

not detected with these methods.

How MHE Can Affect Each Part of the Body

Pick a bone this link will show you all the bones in the body

MHE usually manifests during early childhood more commonly with several knobby, hard,

subcutaneous protuberances near the joints.

The likelihood of involvement of various anatomical sites as observed in a large series is as

follows: Skeleton: The Bones

Anatomical

locationPercentage of

involvementDistal femur 70 Proximal tibia 70 Proximal fibula 30 Proximal Humerus 50 Scapula 40 Ribs 40 Distal radius and

ulna30 Proximal femur 30 Phalanges 30 Distal fibula 25 Distal tibia 20 Bones of the foot 10-25 The Skull

Lesions in the skull, although reported are extremely rare. Mandibular osteochondromas,

typically of the condyle, skull wall lesions and even intracranial lesions have been reported.

Affects of MHE on Skull:

Exostoses can cause problems if they compress or entrap cranial nerves or cause extrinsic

compression on the brain. Effects can range from bumpy external lesions that cause cosmetic

problems, compression of adjacent structures, cranial nerve involvement and even focal

neurological deficits due to compression. Even seizures are likely due to intracranial lesions.

Diagnostic Procedures:

The orthopedist will manually feel for exostoses along the outer table of the skull, check

movements of the mandible and also of the upper cervical spine. The orthopedist will also check

cranial nerve function and perform a thorough neurological evaluation. X-rays or other imaging

tests including CT and MRI may be ordered.

Possible Treatment Options:

Minor lesions on the outer table of the skull that are flat can sometimes be closely observed.

Bigger lesions on the skull, mandibular lesions causing TM joint instability, and intracranial lesions causing pressure signs may need to be removed by neurosurgical

intervention.

Upper cervical spinal tumors, especially of the atlanto-occipital region may be dealt with by orthopedists. Decompression and or stabilization may be performed as required.

What Parents Should Watch Out For:

Pain. Is your child experiencing pain from exostoses?

Visible lumps on the face or skull.

Any symptoms of tingling, numbness, weakness in the hands or legs suggestive of focal deficits.

Visible lumps on the face or skull. Episodes of seizures or findings of cranial nerve involvement like altered smell, taste, ringing in ears etc.

Problems in chewing, restricted motion of the jawbone or instability of the mandible.

Parents can ask dentists and orthodontists to be on the lookout for signs suggestive of jawbone instability or joint involvement during their office visits especially in symptomatic

cases.

Spine

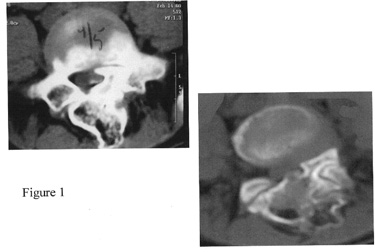

The spine extends from the base of the skull to the tailbone. Spinal exostoses are rare (Figure

1). Spinal cord impingement is also a rare, but documented, complication of MHE. Cervical,

thoracic or lumbar region can be affected. Scoliosis secondary to spinal osteochondromas and

instability has been reported.

Affects of MHE on the Spine: more views of the spine can be seen on the MHE

Affects of MHE on the Spine: more views of the spine can be seen on the MHE

Research Foundation image gallery

This section of the body is not commonly involved with MHE. Involvement of isolated vertebrae

has been noted. Affects can range from instability to neural root or cord compression that can

manifest as tingling, numbness or weakness in the involved roots or even major neurological

deficits like paraparesis or quadriparesis in untreated cases. Rarely compression effects in the

form of dysphagia, intestinal obstruction or urinary symptoms may occur.

Diagnostic Procedures:

With any of the red flags mentioned earlier, the orthopedist will perform a thorough spinal and

neurological evaluation. Plain x-rays of the spine and if required, advanced imaging may be

performed. The presences and extent of the lesion are best delineated with CT, while MRI of the

spinal cord demonstrates the area of spinal cord impingement. In rare cases of peripheral nerve

compression electromyography may be performed to check status of the nerve.

Possible Treatment Options:

Minor lesions not causing compressive symptoms or neurologic manifestations may be kept under close observation.

Progressive scoliosis and spinal instability may need to be treated with surgical stabilization involving spinal fusion.

What Parents Should Watch Out For:

Any red flags in terms of tingling, numbness, weakness, night pain or bladder and bowel changes and get them evaluated.

Any deformity in the spine or evidence of shoulder or pelvic imbalance.

Gait or posture disturbances. Remember that gait and posture disturbances can be caused by hip or leg exostoses as well (due to either limb-length discrepancy or deformity)

and do not necessarily mean tumors in the spine. In any case evaluation by a clinician is

important.

Ribs and Sternum

Affects of MHE on the ribs and sternum:

The typically flat bones of the ribs are prone to effects of MHE, with approximately 40% of MHE

patients having rib involvement. Prominent chest wall lesions are common although intrathoracic

lesions including rare presentations like spontaneous hemothorax (build-up of blood and fluid

in the chest cavity) as a result of rib exostoses have been described. Typically, these lesions

create issues of cosmesis due to their obvious visibility. Other symptoms may include shortness

of breath and other breathing difficulties, pain when taking a deep breath, when walking or

exercising, or pain from exostoses “catching”.

Diagnostic Procedures:

The orthopedist will probably manually feel for exostoses along the chest wall and the ribcage.

Size and extent of the lesions are noted. A thorough pulmonary evaluation is warranted in all

cases when specific symptoms of cough, chest pain or breathing problems are encountered. X-

rays or other imaging tests may be ordered.

Possible Treatment Options:

Pulmonary: when there are severe breathing difficulties with increasing chest pain.

Minor bumps can sometimes be kept under observation.

Cosmetic problems, rapid increase in size, large size, and signs of compression are some indications for early removal.

Consult may be required with specialists:

Thoracic surgeons: when intrathoracic (within the chest wall) exostoses may need to be excised.

What Parents Should Watch Out For:

Breathing difficulties, shortness of breath.

Pain when taking deep breath.

Shoulder girdle

The scapula is a fairly common site (40%) of involvement in MHE. The lesions may be located onthe anterior or posterior aspect of the scapula. Anterior scapular lesions may lead to discomfort

during scapulothoracic motion. Winging of the scapula due to exostoses has been described.

Clavicle (collar bone) involvement has also been described (5% cases).

What is winging?

The scapula (also known as shoulder blade) is a triangular flat bone that is located in the upper

back and takes part in forming the shoulder joint. The scapula usually lies flat on the chest wall

without any prominence. Winging of the scapula is a phenomenon when a part of the scapula

including the inferior angle becomes prominent either at rest or during movements.

The two most common causes for this are

Exostosis on the inner (chest wall) aspect of the scapula.

Damage to the nerve (long thoracic) causing weakness or paralysis of muscles (serratus anterior) attached to the scapula.

Diagnostic Procedures:

The orthopedist will probably manually feel for exostoses along the outer aspect of the shoulder

blade. Some limited areas of the inner aspect are amenable to clinical examination. Range and

feel of the scapulothoracic motion is helpful in clinical assessment. It is important to check

individual groups of scapular muscles to rule out nerve compression leading to winging of

scapula. X-rays (including special tangential views of the scapula) or other imaging tests may be

ordered.

Possible Treatment Options:

Both outer aspect lesions and inner ones may need excision in symptomatic cases. Smaller lesions on outer aspect amenable to clinical palpation may be observed with regular clinical

follow-up.

What Parents Should Watch Out For:

Crunching or crackling sound when moving that area.

Pain.

Tingling, numbness.

Arms

Upper Arm (X-rays) (Humerus)

Elbow

Forearm (Radius and Ulna)

Wrists The arm bone is called the humerus while the forearm bones are the radius (curved bone) and

the ulna (straighter bone of the two). To view more x-rays please view the MHE Research

Foundations image galery

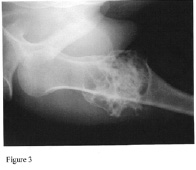

Osteochondromas of the arm are often readily felt but rarely cause neurologic dysfunction.

(Figure 2). Osteochondromas of the upper extremities frequently cause forearm deformities.

The prevalence of such deformities has been reported to be as high as 40-60%.

Disproportionate ulnar shortening with relative radial overgrowth has been frequently described

and may result in radial bowing. Subluxation or dislocation of the radial head is well-described

sequelae in the context of these deformities.

The length of forearm bones inversely correlates with the size of the exostoses. Thus, the

larger the exostoses and the greater the number of exostoses, the shorter the involved bone.

Moreover, lesions with sessile rather than pedunculated morphology have been associated with

more significant shortening and deformity. Thus, the skeletal growth disturbance observed in

MHE is a local effect of benign growth. Exostoses in the forearm are known to involve both the

radius and the ulna. Since movements of the forearm (pronation and supination) are

dependant on the radius moving in an arc of motion around the ulna, mobility may be restricted

depending upon the severity of presentation. Also the lower end radius exostoses can lead to

compression of the median nerve (in a closed space at the level of the wrist called the carpal

tunnel) and present with weakness, tingling and numbness in the hand. Exostoses in the carpal

bones can seriously hamper the wrist motion and cause pain.

Complete dislocation of the radial head is a serious progression of forearm deformity and can

result in pain, instability, and decreased motion at the elbow. Surgical intervention should be

considered to prevent this from occurring. When symptomatic, this can be treated in older

patients with resection of the radial head.

Diagnostic Procedures:

The orthopedist will clinically feel for exostoses along the arm, elbow and forearm, and check

range of motion (“ROM”) by moving the arm in different directions. The orthopedist will also

check measurements on each arm and forearm to see if there is a difference. X-rays or other

imaging tests may be ordered.

Possible Treatment Options:

Indications for surgical treatment include painful lesions, an increasing radial articular angle, progressive ulnar shortening, excessive carpal slip, loss of pronation, and increased radial

bowing with subluxation or dislocation of the radial head Minor lesions can sometimes be

observed with careful follow up.

Bowing and some length discrepancies and be treated with a surgical procedure called “stapling,” where surgical staples are inserted into the growth plate of the bone growing

faster than the other. This will hopefully give the slower growing bone the chance to “catch

up” and the forearm will straighten over time.

Limb Lengthening with a fixator.

Resection of the radial head.

Excision of exostoses.

Osteotomy

Epiphysiodesis

Non-surgical measures for treatment of soft-tissue compression, irritation or inflammation (anti-inflammatories, heat, rest, etc.)Adaptive devices to aid those with shortened

forearms, such as grippers, long-handled sock aides, etc.

What Parents Should Watch Out For:

Any red flags in terms of sudden increase in size of swelling, pain, nerve compression, tingling, numbness, or weakness.

Possibility of exostoses irritating or catching on overlying tissue, such as muscles, tendons, ligaments, or compressing nerves.

Loss of range of motion

Pain

Difficulty and/or pain when raising arm(s), lifting, carrying

Please also refer to the MHE Research Foundations fixator information guide. Their are alsomore links located in the Green Table at the bottom of the orthopaedic page and in the tool bar

Hands and Fingers

Hand involvement in MHE is common. Fogel et al. observed metacarpal involvement and

phalangeal involvement in 69% and 68%, respectively, in their series of 51 patients. In their

series of 63 patients, Cates and Burgess found that patients with MHE fall into two groups:

those with no hand involvement and those with substantial hand involvement averaging 11.6

lesions per hand. They documented involvement of the ulnar metacarpals and proximal

phalanges most commonly with the thumb and distal phalanges being affected less frequently.

While exostoses of the hand resulted in shortening of the metacarpals and phalanges,

brachydactyly was also observed in the absence of exostoses.

Diagnostic Procedures:

The orthopedist will manually feel for exostoses in the hands and check range of motion

(“ROM”) in different directions. X-rays or other imaging tests may be ordered.

Possible Treatment Options:

Isolated lesions growing rapidly, or interfering with the smooth motion of tendons or joint motion may need to be excised. Multiple surgeries for small, insignificant lesions is usually

not advocate.

Occupational therapy, physical therapy.

Use of pencil grips, laptop computers, and other adaptive devices.

What Parents Should Watch Out For:

Complaints of pain when writing.

Some children will not complain of pain, but will have poor penmanship, write slowly, avoid writing, etc. Parents should also observe how the child holds writing and eating utensils.

Difficulty in rotating hand(s),

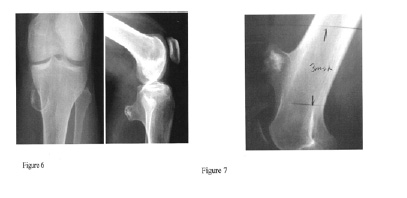

Pelvic Girdle (Hips and Pelvis) Osteochondromas of the proximal femur (Figure 3) may lead to progressive hip dysplasia. There have

Osteochondromas of the proximal femur (Figure 3) may lead to progressive hip dysplasia. There have

been reported cases of acetabular dysplasia with subluxation of the hip in patients with MHE. This results

from exostoses located within or about the acetabulum that may interfere with normal articulation.

Pelvic lesions (Figures 4 and 5) may be found on both the inner as well as outer aspect of the

Pelvic lesions (Figures 4 and 5) may be found on both the inner as well as outer aspect of the

pelvic blades. Large lesions may cause signs of compression, both vascular and neurological. There

have also been reports of exostoses interfering with normal pregnancy and leading to a higher

rate of Cesarean sections. To view more x-rays please view the MHE Research Foundations

image galery

Diagnostic Procedures:

Manual palpation is sometimes very difficult in these deep lesions. The orthopedist will check range

of motion (“ROM”) by manipulating (moving) the leg in different directions. The orthopedist will

also check measurements on each leg to see if there is a difference in limb lengths. X-rays or other

imaging tests may be ordered.

Possible Treatment Options:

Minor length discrepancies can sometimes be effectively treated with the use of orthotics (specially made shoes or lifts that will equalize leg length).

Bowing and some limb length discrepancies can be treated with a surgical procedure called “stapling,” where surgical staples are inserted into the growth plate of the leg bone growing

faster than the other. This will hopefully give the slower growing bone the chance to “catch

up” and the limb will straighten over time.

Limb Lengthening with a Fixator. Please see the lower limb & forearm, use of fixators guide located in the website tool bar above

Pelvic lesions of concern may need to be surgically excised.

Osteotomies.

Hip replacement.

What Parents Should Watch Out For:

Limping

Pain in hips, back, legs.

Pain, discomfort, difficulty in sitting.

Inability to sit “tailor” style. The position known as Indian or tailor style involves both feet bent inwards and under the body, crossing each other at the ankle.

Stiffness in hips and/or legs after sitting.

Pain and fatigue from walking.

Legs and Knees

Femur

Knees

Lower Leg (Tibia and Fibula)

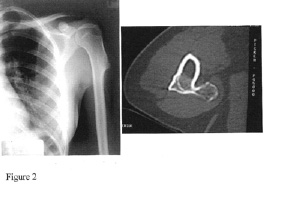

Genu Valgum or Knock-knee deformities are found in 8-33% of patients with MHE. Genu

Genu Valgum or Knock-knee deformities are found in 8-33% of patients with MHE. Genu

valgum is defined as a mechanical malalignment of the lower limb when the knees knock against

each other and the legs are pointed away from the body. Although distal femoral involvement is

common, the majority of cases of angular limb deformities are due mostly to lesions of the tibia

and fibula (Figures 8,9 & 10), which occur in 70-98% and 30-97% of cases, respectively. The

fibula has been found by Nawata et al. to be shortened disproportionately as compared to the

tibia, and this is likely responsible for the consistent valgus direction of the deformity. Genu

varum or Bowlegs may also occur in some cases. This is defined as a mechanical malalignment of

the lower limb when the knees drift away from the body and the legs are bowed and close

together.

To view more x-rays please view the MHE Research Foundations image galery

To view more x-rays please view the MHE Research Foundations image galery

Diagnostic Procedures:

The orthopedist will probably manually feel for exostoses along the leg, and check range of

motion (“ROM”) by manipulating (moving) the leg in different directions. The orthopedist will

also check measurements on each leg to see if there is a difference. X-rays or other imaging

tests may be ordered.

Possible Treatment Options:

Minor length discrepancies can sometimes be effectively treated with the use of orthotics (specially made shoes or lifts that will equalize leg length).

Bowing and some limb length discrepancies and be treated with a surgical procedure called “stapling,” where surgical staples are inserted into the growth plate of the leg bone

growing faster than the other. This will hopefully give the slower growing bone the chance

to “catch up” and the limb will straighten over time.

Limb Lengthening with a Fixator. Please see the lower limb & forearm fixator guide and other links located in the website tool bar above.

Excision of exostoses

Osteotomy

What Parents Should Watch Out For:

Any red flags in terms of sudden increase in size of swelling, pain, nerve compression, tingling, numbness, or weakness.

Possibility of exostoses irritating or catching on overlying tissue, such as muscles, tendons, ligaments, or compressing nerves.

Leg cramps, bluish color, difference in skin temperature may indicate compression of a artery (most often the popliteal artery, located behind the knee).

Compression of the peroneal nerve, which runs along the outside of the leg, can cause a condition known as “drop foot”, in which the foot cannot voluntarily be flexed up.

Compression can be caused by exostoses growth, or as a complication of surgery.

Limping, pain when walking.

Bowing of leg(s)

Exostoses on inside of legs bumping into each other.

Exostoses interfering with normal movements, either by blocking movement or by causing pain (bending, sitting, walking up or down stairs).

Pain and fatigue when walking.

Gait problems (awkwardness, limping, slow movements, etc.)

Ankles

Valgus deformity of the ankle is also common in patients with MHE and is observed in 45-54% ofpatients in most series. This valgus deformity can be attributed to multiple factors including

shortening of the fibula relative to the tibia. A resulting obliquity of the distal tibial epiphysis

and medial subluxation of the talus can also be associated with this deformity, while

developmental obliquity of the superior talar articular surface may provide partial compensation.

Diagnostic Procedures:

The orthopaedist will probably manually feel for exostoses along the leg, and check range of

motion (“ROM”) by manipulating (moving) the leg in different directions. The orthopaedist will

also check measurements on each leg to see if there is a difference. X-rays or other imaging

tests may be ordered.

Possible Treatment Options:

Minor length discrepancies can sometimes be effectively treated with the use of orthotics (specially made shoes or lifts that will equalize leg length).

Bowing and some limb length discrepancies and be treated with a surgical procedure called “stapling,” where surgical staples are inserted into the growth plate of the leg bone

growing faster than the other. This will hopefully give the slower growing bone the chance

to “catch up” and the limb will straighten over time.

In more advanced cases, excision of exostoses with early medial hemiepiphyseal stapling of the tibia in conjuction with exostosis excision can correct a valgus deformity at the ankle of

15° or greater associated with limited shortening of the fibula.

Fibular lengthening has been used effectively for severe valgus deformity with more significant fibular shortening, (i.e. when the distal fibular physis is located proximal to the

distal tibial physis).

Supramalleolar osteotomy of the tibia has also been used effectively to treat severe valgus ankle deformity.

Growth of exostoses can also result in tibiofibular diastasis that can be treated with early excision of the lesions.

What Parents Should Watch Out For:

Limping, pain when walking.

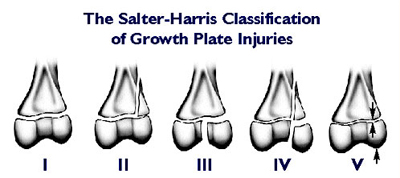

Recurrent falls and instability while walking on uneven surfaces. Parents should be aware that falls could result in what are known as Salter-Harris Fractures / (Growth plate

fractures) this has been seen to occur in children with MHE / MO / HME. If your child falls

and the pain is occurring around the growth plate area of the joint, this should be checked

by your orthopaedic doctor. As these type of fractures can also lead to bone deformity.Disclaimer: While many find the information useful, it is in no way a substitute for professional

medical care.The information provided here is for educational and informational purposes only. This

website does not engage in the practice of medicine. In all cases we recommend that you consult your

own physician regarding any course of treatment or medicine.

Email the webmaster: webmaster@mheresearchfoundation.org

Materials on this website are protected by copyright

Copyright © 2008 The MHE Research FoundationThis file will print 17 pages

Feet and Toes

Osteochondromas may occur in the tarsal and carpal bones, however they are often less

apparent. Relative shortening of the metatarsals, metacarpals, and phalanges may be noted.

Diagnostic Procedures:

Plain radiographs are probably more useful in defining the extent of involvement of the small

bones of the feet in MHE. Other imaging studies may be ordered as and when required.

Possible Treatment Options:

Large bumps can be surgically excised when symptomatic.

Deformities of the foot (like hallux valgus) may be corrected by stapling of the growing epiphysis in younger children or by surgical osteotomy in older patients.

What Parents Should Watch Out For:

Compression of the peroneal nerve, which runs along the outside of the leg, can cause a condition known as “drop foot”, in which the foot cannot voluntarily be flexed up.

Compression can be caused by exostoses growth, or as a complication of surgery.

In general

“What Parents Should Watch Out For”

If your child is limping, check to see if it is due to an injury, or is something that is occurring and continuing without obvious reason. Limping may signal a limb length

discrepancy or other problem.

Bowing of one or both legs.

Mobility problems. Is your child experiencing pain when walking or running?

Pain. Is your child experiencing pain from exostoses that bump each other? Is your child experiencing pain during certain activities, or pain at night. If so, keep a pain diary.

Any red flags in terms of sudden increase in size of swelling, pain, nerve compression, tingling, numbness, or weakness

What Adults Should Be Aware Of:

Sudden growth in an existing exostosis and pain can be symptomatic of a malignant transformation. It is smart to check out any changes with your orthopaedist. However,

it is important to remember that chondrosarcoma is rare.

Years of wear and tear on joints can result in chronic pain. There is also the possibility of exostoses irritating or catching on overlying tissue, such as muscles, tendons, ligaments,

or compressing nerves. Possible Treatment Options for these common problems, include

pain medications, physical therapy (including stretching, strengthening and modalities),

heat, rest, bracing (supportive orthosis acting as load sharing devices) etc.

Glossary of terms and procedures:

Synonyms of multiple exostoses: A number of synonyms have been used for this disorder

including osteochondromatosis, multiple hereditary osteochondromata, multiple congenital

osteochondromata, diaphyseal aclasis, chondral osteogenic dysplasia of direction, chondral

osteoma, deforming chondrodysplasia, dyschondroplasia, exostosing disease, exostotic

dysplasia, hereditary deforming chondrodysplasia, multiple osteomatoses, and osteogenic

disease.

Anterior: Situated in the front; forward part of an organ or limb

Ball and socket joints: Movable (synovial) joints, such as hips and shoulders, that allow a

wide range of movement.

Bilateral: having two sides or pertaining to both sides.

Biopsy: Take a piece of the lesion to study the histological characteristics.

Cartilage: Form of connective tissue, more elastic than bone, which makes up parts of the

skeleton and covers joint surfaces of bones.

Coxa-valga: When the thighbones are drawn farther apart from the midline due to an increase

in the neck-shaft angle of the femur.

Coxa-vara: When the thighbones are drawn closer to the midline due to a decrease in the neck-

shaft angle of the femur.

Dislocation: When the normal articulating joint surfaces have lost total contact.

Distal: Away from the midline or the beginning of a body structure (the distal end of the

humerus forms part of the elbow).

Epiphysiodesis: To surgically stop the growth of the growing end of the bone either

temporarily or permanently.

Excision: To surgically remove the lesion.

Genu-valgum: Knock-knees.

Genu-varum: Bowlegs.

Hinge joints: movable joints, such as knees and elbows, that allow movement in one direction.

Limb-lengthening: Process of increasing the length of bones using one of the various devices.

Also view

lower limb & forearm fixator guide and other links located in the website tool bar above.

LLD: Limb-length discrepancy- difference in limb lengths.

Medial: Pertaining to the middle or toward the midline.

MHE: An autosomal-dominant disorder manifested by multiple osteochondromas and frequently

associated with characteristic skeletal deformities.

Osteochondromas: Cartilage capped tumors found commonly at rapidly growing ends of bones.

Osteotomy: The surgical division or sectioning of a bone.

Pedunculated: Lesion with a stalk connecting it to the main bone.

Posterior: Situated in the back; back part of an organ or limb

Proximal: Near the midline or beginning of a body structure (the proximal end of the humerus

forms part of the shoulder).

Sessile: Lesion without a stalk connecting it to the main bone.

Stapling: Process of insertion of a mechanical device (staple) following surgical intervention.

Subluxation: When the joint surfaces are still facing each other but not totally in contact.

Graphic provided by http://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Growth_Plate_Injuries/graphics/growth-plate.jpg